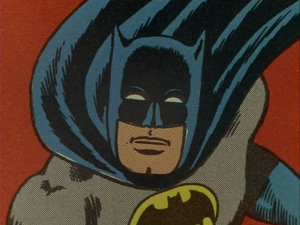

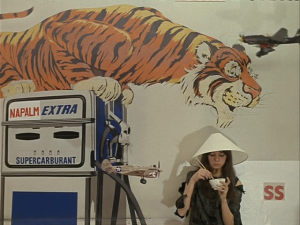

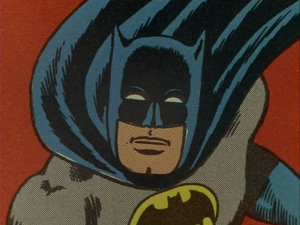

Next to re-appropriated images of commercial advertisements and abstracted signs, the comic panel plays a major role in Jean-Luc Godard’s construction of two-dimensional mise-en-scène. Whether it be an image of a diamond-eyed tiger in Pierrot le fou (1965), a comic panel of a woman standing up against a Rolls-Royce in Deaux ou trios choses que je sais d’elle (Two or Three 3 Things I Know About Her, 1967), or Batman and Captain America taking out their imperialist vengeance on the Vietnamese while Marxist-Leninists scrawl their edicts on the white-walls of an apartment à la word balloons in La Chinoise (1967), these citations evoke an image of Godard as an artist of eclectic taste. However, as with most of Godard’s citations, comic strip images are not simply fodder for aesthetic collage. There is an underlying tension in these citations that, like the work of his contemporary, American pop artist Roy Lichtenstein, is concerned with the role of art and visual signs more generally and their roles in contemporary society.

Next to re-appropriated images of commercial advertisements and abstracted signs, the comic panel plays a major role in Jean-Luc Godard’s construction of two-dimensional mise-en-scène. Whether it be an image of a diamond-eyed tiger in Pierrot le fou (1965), a comic panel of a woman standing up against a Rolls-Royce in Deaux ou trios choses que je sais d’elle (Two or Three 3 Things I Know About Her, 1967), or Batman and Captain America taking out their imperialist vengeance on the Vietnamese while Marxist-Leninists scrawl their edicts on the white-walls of an apartment à la word balloons in La Chinoise (1967), these citations evoke an image of Godard as an artist of eclectic taste. However, as with most of Godard’s citations, comic strip images are not simply fodder for aesthetic collage. There is an underlying tension in these citations that, like the work of his contemporary, American pop artist Roy Lichtenstein, is concerned with the role of art and visual signs more generally and their roles in contemporary society.

Moreover, Godard’s comic strip mise-en-scène is not a static aesthetic entity. Made in USA (1966) utilizes re-contextualised images of comic strips as a means of graphic punctuation and engages with a style of comic strip framing, while the citations of La Chinoise tend to serve as icons and symbols of imperialist ideology. Godard’s shift from comic strip citation to mimesis would become full blown by 1972, as Tout va bien, his collaboration with Jean-Pierre Gorin, will exemplify. With the objective of elaborating upon this shifting aesthetic, I would like to embark on a formal analysis of a sequence from each of these three films while drawing on the frameworks of pop art, post-modernism, and comic strip semiotics.

1. Made in USA

“[In reference to Michelangelo Antonioni's The Red Desert] I don’t think I know how to manufacture a film like that. Except that maybe I am beginning to be tempted to try something of the sort. Made in USA was the first sign of that temptation. That’s why it wasn’t understood, the audience watched it as if it were a representational film, whereas it was something else.” -Jean-Luc Godard (1)

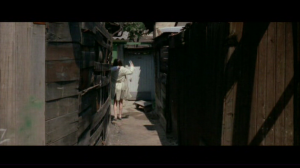

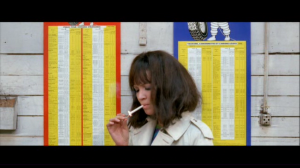

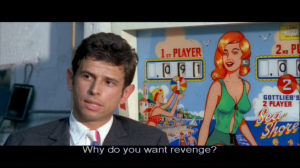

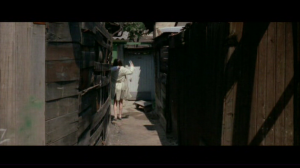

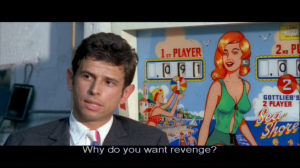

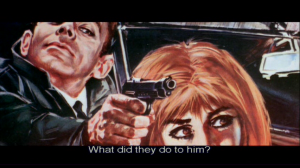

While Pierrot le fou marks the beginnings of Godard’s engagement with the comic strip with its citations of The Nickel Footed Gang and Gerald Norton, and Alphaville, une étrange avenutre de Lemmy Caution (Alphaville, a Strange Adventure of Lemmy Caution, 1965) utilises the comic strip hero and the hardboiled detective as templates for Lemmy Caution, Made in USA marks the beginnings of what Godard described as an attempt to “pass across to the inside of the image” with the objective of complicating systems of visual representation. (2) For this formal analysis of Made in USA, I have chosen the sequence of Paula Nelson (Anna Karina) making her way down the street, only to be knocked out by an unseen assailant, and waking to engage in a dialogue with Richard Widmark (László Szabó). For the sake of clarity, frame re-productions with shot numbers and approximate times have been provided:

(Shot 1A and 1B, Paula walks out and is knocked unconscious, 34:33-34:57)

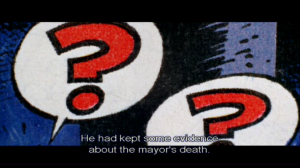

(Shot 2, “!…Bing” Insert, 34:57-34:58) (Shot 3, Paula Awakens, 34:58-35:58)

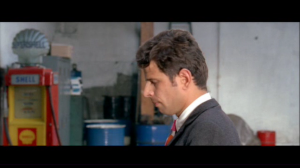

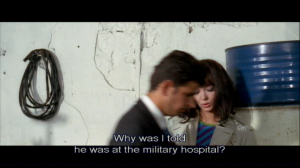

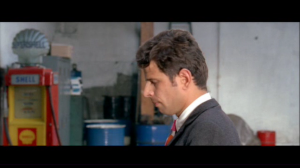

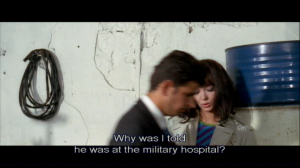

(Shot 4, Widmark, 35:58-36:13) (Shot 5, Widmark and Paula, 36:13-36:32)

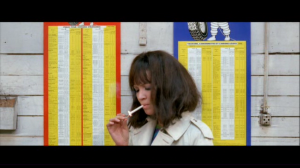

(Shot 6, Paula, 36:32-36:57) (Shot 7, Widmark, 36:57-37:12)

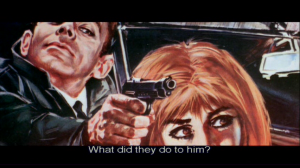

(Shot 8, Pulp Art Insert, 37:12-37:17) (Shot 9, Paula and Widmark, 37:17-37:30)

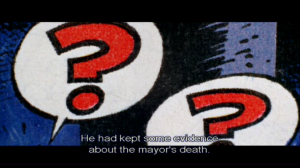

(Shot 10, “?” Insert, 37:30-37:44) (Shot 11: Widmark, 37:44-37:56)

This sequence illustrates Godard’s quick shift of aesthetic modes. Shot 1, like the two shots of Paula in the garden preceding it, is held on screen for a relatively long duration (over twenty seconds) and features a panning movement that tracks Paula as she walks down the sidewalk and into an alley, where she is knocked unconscious. Godard’s camera movement here, and in the preceding shots, leans on the reality of the setting in its fidelity to space and time via the motion of the camera and the absence of a cut. In this sense, Godard’s fidelity to space and time would seem to be a perfect illustration of Andrè Bazin’s aesthetic model of putting faith in reality over the image. Godard however, as his theory of montage and mise-en-scène in his essay “Montage My Fine Care” establishes, refuses to plant his aesthetic flag in either camp, as “mise en scène automatically implies montage.” (3) Indeed, as the sequence progresses into shot 2, Godard inserts a one-second extreme close-up of an abstracted comic panel simply reading “!..Bing,” putting his faith in the image to complete his cinematic sentence.

The image, neither seen before this sequence nor will it be after, is accompanied by a loud thudding sound. The insert not only represents, like it would in its original context, a punctuation of the action but as an indication of Godard’s shift into the realm of the image. In shot 3, Paula awakens, asking herself where she has been taken. While the shot is temporally quite long (nearly one minute), the camera is static and its tight framing keeps the spectator from discovering her surroundings. Shot 3 marks the progression of the abstraction established in shot 2 as the subsequent shots are constructed by a static camera with the only movement coming from Paula and Widmark walking in and out of frame during a conversation.

The shot breakdown of shots 3 through 7 corresponds to the sequence of images a comic book artist would lay out a conversation between two characters.

(Figure 1: The Origin of The Spirit) (4)

Comic strips, while similar to film in their reliance on sequential images to relay a narrative, do not rely on the cinematic equivalent of shot/reverse shot or eye line matching to formally carry a conversation. This is mainly due to the comic strip, book, or graphic novel’s limitation of physical space: a layout depending on shot/reverse shots would simply take up too many panels, making for unwieldy reading. Take, for an example, the above opening page from Will Eisner’s The Spirit. Denny Colt walks into the office of police commissioner Dolan and engages in a conversation regarding the location of an escaped villain. Note, however, that Eisner never utilises a shot/reverse shot pattern to secure a continuity of space. In fact, he breaks the cinematic 180 degree rule in the transition from panel 3 to panel 4. Moreover, Eisner’s panels are composed towards the reader, frontally.

Godard, in this sequence, is not merely citing comic strip graphics in shots 2 and 10. Rather, the spatial construction of the dialogue between Paula and Widmark (shots 3-7, 9, and 11) is a form of mise-en-scène based on the spatial layout of a comic strip. If Godard were to freeze-frame the shots and place the dialogue over them, the result would be a cinematic equivalent to comic layout. The reliance on primary colours (red, white, and blue), the flatness of the compositions, and the absence of a shot/reverse shot pattern to preserve the conversation and the space the characters magnify this effect. The spatial incoherence of this sequence is magnified in the larger body of the film by the labyrinthine quality of its plot. Indeed, the plot of Made in USA is largely irrelevant. Instead, what Godard leaves the viewer to ponder is perhaps best illustrated in a later exchange between Paula and Widmark. Paula, trying to make sense out of the events that resulted in the murder of her former lover, proclaims, “I don’t get it. I don’t get it,” to which Widmark responds, “Mise-en-scène. Mise-en-scène. Oh, mise-en-scène.”

Of course, Godard’s turn from traditional narrative construction towards film form is not very surprising. Before 1967, Godard’s formal preoccupations often found themselves wrapped in the security blanket of a film genre, most often the French policier or film noir, and Made in USA is no exception. As James Roy MacBean observes in his review of the film, “Godard is well aware that the ordinary film-viewer’s habit of concentrating on the anecdotal structure of ‘plot’ often presents a formidable obstacle to his getting inside the film and understanding the subtle language of colour, composition, and light.” (5) Yet, as MacBean’s observation alludes, to note that Godard is less concerned with plot and storytelling in Made in USA is not simply to write the film off as a simple formal exercise. While the plot is nearly meaningless, the logic of the form is not and, as MacBean writes, the formal logic behind it is driven by an investigation of the communicative sign, another Godardian trope that would manifest itself perfectly in Two or Three Things I Know About Her.

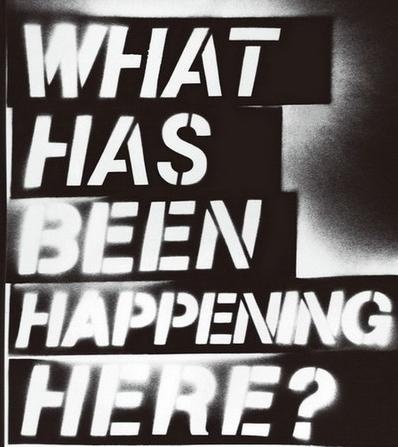

Godard’s investigation of the sign in Made in USA is, as often is the case, distrustful of spoken language and, in the binary between audio and visual, often finds him putting his faith in the image. In Made in USA, Godard shows his distrust of language via numerous devices: the overwhelming of dialogue by a phone ringing or a jet flying over- by, the audible distortion of the film’s key piece evidence: a voice recording, and in a scene between Paula, a labourer, and a barman. Godard, however, does not only undercut the audible with the audible but with the visual as well. For instance, shot 10, the question mark insert of the above cited sequence, is held on screen for fifteen seconds as Paula and Widmark exchange questions regarding the death of her husband as a cinematic means of punctuation. Via its function, quite literally as a question mark, Godard attempts to provide a gateway to pass to the “inside of the image,” much like the American pop art of Roy Lichtenstein.

(Figure 2: Lichtenstein’s “Blam,” 1962) (Figure 3: “Drowning Girl,” 1963)

Lichtenstein, like Godard, utilised citations of comic strips to produce a heightened awareness towards the visual sign. Yet, as Daniel Yacavone writes in his study of the two artists, Godard and Lichtenstein’s modes of citation differ. Godard, by citing an image and utilising it as a piece for montage, re-contextualises a pre-existing image, while Lichtenstein’s citation ignores an image sequence at all, abstracting a single panel onto a single canvas. (6) While I would agree with him, I would also add that each of the citations of Godard and Lichtenstein inspire different results. According to art historian Jonathan Fineberg, “Lichtenstein was not painting things but signs of things. His true subject is…the terms of their translation into the language of media and the implications of that metamorphosis.” (7) In contrast to Lichtenstein, Godard’s citation in Made in USA does not seem to be questioning the implications of that translation and the complications that arise from its aesthetic. While his objective may have been to produce a film that went beyond representation in a visual sense, the end result is quite the opposite: Godard criticises the representational qualities of a film’s soundtrack in favour of underlining the visual by utilising the comic strip image as a means to literalise. However, his use of comic strip mise-en-scène would evolve into a more successful investigation of the visual sign in Two or Three Things I Know About Her and, as will now be discussed, La Chinoise.

2. La Chinoise

“To live in society today is like living in one enormous comic-strip.”

-Jean-Luc Godard (8)

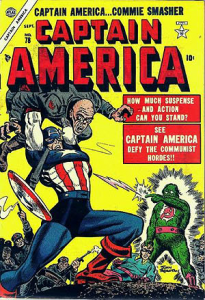

Amongst the numerous sequences in La Chinoise that would be relevant to this area of inquiry, for the sake of brevity I would like to focus on one sequence and one reoccurring aesthetic characteristic. I would first like to turn to the sequence of analysis: the machine gun montage of Batman, Sgt. Fury, and Captain America. Once again, frame reproductions of individual shots and durations have been noted for clarity:

(Shot 1: Yvonne, 35:06-35:12) (Shot 2: Guillaume, 35:12-35:17)

(Shot 3: Batman, 35:18-35:18) (Shot 4: Sgt. Fury/Capt. America, 35:18-35:19)

[Note: Shots 3 and 4 alternate every few frames, accompanied by an audio track of machine gun fire, from 35:18-35:28. They roughly go through sixteen alternations.]

(Shot 5: Yvonne, 35:28-35:41)

This sequence, as the noted durations will attest, is quite short at roughly thirty-seconds, particularly significant for a film whose “Second-Act” (for lack of a better term) climaxes with static shots of two people talking on a train (one shot lasts nearly four minutes). While the form of citation obviously echoes the use of the “!…Bing” and the “?” panels in Made in USA by abstracting the individual panels from their larger sequence and the sequence once again marks Godard’s faith in the image and montage over a Bazinian approach to mise-en-scène, the approach to the citation of these comic strips has evolved with regard to how the form intersects with the content of the film as a whole.

Whereas the comic strip citation in Made in USA served as a form of visual punctuation for the scene, visually underlining the action of Paula being assaulted and her dialogue with Widmark. The citation in the La Chinoise sequence, on the other hand, is drenched in the political, a reading no doubt influenced by the film’s investigation of Marxist-Leninist ideology. If Godard’s use of citation in Made in USA was, with regard to the work of Lichtenstein, more concerned with translation of media, citation in La Chinoise is concerned with the consequences of that translation. The citation of famous superheroes from two prevalent American comic strip publishers, DC (Batman) and Marvel (Sgt. Fury and Captain America) in the context of this scene moves beyond the visual literalisation of Made in USA.

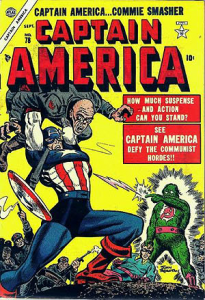

(Figure 4: Captain America…Commie Smasher) (9)

Godard’s utilisation of the superheroes here, particularly that of Captain America, is both what comic book practitioner and theorist Scott McCloud describes as an icon, or “any image used to represent a person, place, thing, or idea” but also serves as a symbol that represents American political ideology towards the Vietnam conflict. (10)

While this hypothesis relies on speculation regarding Godard’s familiarity with American comic strips during the production of La Chinoise, the Captain America comics of the 1950s and 60s depicted a hero whose chief enemy was Communism. In the early 1960s, Captain America joined Sgt. Nick Fury and his “Howling Commandos” to take part in the Vietnam war. Godard’s use of Captain America and Sgt. Fury in this montage seems to be aware of the narratives of the original source material, as he places the montage directly after Guillaume’s (Jean-Pierre Léaud) “exercise” in which he re-enacts the Vietnam war by putting on different pairs of sunglasses, each with one of the participating nation’s flag painted on them, and critiquing their role in the conflict.

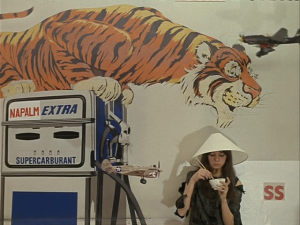

Godard foreshadows the comic strip montage as Guillaume reads from Mao’s Little Red Book, quoting, “Imperialism and all reactionaries are paper tigers. They appear ferocious but they’re not really so powerful.” When asked if Vietnam is a character in the play, Guillaume snaps his fingers as Godard cuts to Yvonne (Juliet Berto), sporting a lampshade on her head á la Vietnamese conical hat. The shot, number one in the sequence under examination, displays Godard’s wallpaper tiger (also used in Pierrot Le Fou and in the 1967 Weekend) as it overlooks the implied napalm bombing of Vietnam. Godard then cuts back to Guillaume (shot 2), who states, “First a few facts, as truth lies there,” and then begins the comic strip montage.

As the montage, with cuts punctuated by the sounds of a machine gun firing, comes to its end, Godard places the voice of Yvonne over the final shot of Captain America and Sgt. Fury, stating that, “The NLF [National Liberation Front] will win.” The montage sequence illustrates Guillaume’s quotation of Mao by juxtaposing a graphic of a tiger and paper symbols of America’s political ideology, as manifested by Captain America and Sgt. Fury, to illustrate the quotation. Thus, Godard seems to have begun to interrogate the politics inherent in his quotation of the comic strip, a sentiment re-enforced by the sequence’s final shot: Yvonne, hiding behind a bunker constructed out of copies of the Little Red Book, takes a portable radio and transforms it into a machine gun. The imagery of the entire sequence seems to imply that popular art forms not only reflect dominant ideology but also have the potential to be politicised and turned against that ideology.

In his analysis of post-modernism, theorist Fredric Jameson questions the effectiveness of Godard’s use of this type of montage. Jameson writes that, “It is no longer certain…that the heavily charged and monitory juxtapositions in a Godard film – an advertising image, a printed slogan, newsreels, an interview with a philosopher, and the gestus of this or that fictive character – will be put back together by the spectator in the form of a message, let alone the right message.” (11) Yet, as this formal analysis of the machine gun montage hopefully illustrates, Godard’s juxtapositions are not impossible to translate into a message. Of course, whether or not its the “right” message can be argued, but given Godard’s objective, as stated in the opening moments of the film, to confront vague ideas with clear images (Figure 5), the machine gun montage appears to be an attempt and, I would argue, a successful one at utilising the icon/symbol of the American superhero to critique American imperialist ideology.

In a manner reminiscent of Jameson’s critique, Godard scholar Wheeler Winston Dixon asserts that La Chinoise is “a tedious exercise in formalist propaganda…[an] alarmingly naive…embrace of the teachings of Chairman Mao.” However, it would seem that Dixon has not received the “right” message. (12) While Godard may be sympathetic to the revolutionary cause, this does not preserve the ideology of the group from criticism which manifests itself in the film in five ways: four of which being narrative and one being formal. The four narrative events, the suicide of the group’s first chosen assassin Kirilov (Lex de Bruijn), the exile of Henri (Michel Semeniako), Véronique’s (Anne Wiazemsky) unsympathetic symposium with philosopher Francis Jeanson, and the inherent tragedy of her bumbled assassination attempt, all go a long way in undermining an “alarmingly naive” embrace of Maoism.

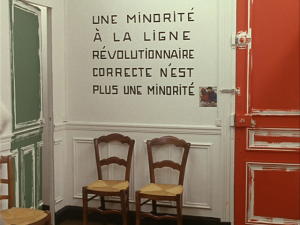

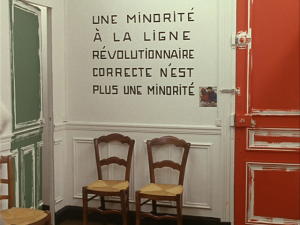

Discussion regarding an analysis of the formal aspect of this critique brings us to the final aesthetic characteristic of La Chinoise up for analysis: Godard’s use of painted text on the walls of the apartment of the Marxist-Leninists. Godard’s aesthetic choice here is uncharacteristic of his earlier works. While Godard often utilizes the insert of a title card as a means of interrogating the text, the direct placement of such rhetorical devices within the physical space of the scene is, I would argue, a rather curious elaboration upon the comic strip mise-en-scène Godard illustrated via his framing in Made in USA. Comics obviously utilize text as not only a form of dialogue (as the word balloons in Figure 1 exemplify), audible punctuation (the “!…Bing” panel), but as a means of narration as well (providing a description of a location for instance).

(Figure 5: “One Must…”, 1:53-2:43) (Figure 6: “A Minority…”, 4:01- 4:51)

Yet, in the comic strip, as theorist David Carrier states, the use of text is normally “a passive element…the words merely accompany the picture, without entering the image.” (13) Carrier’s analysis, an acknowledged generalisation, is helpful here. Godard’s use of title cards, while far from being passive, does not accompany or enter the image due to their spatial and temporal separation. While the titles may provide commentary, they do not, like the form of mise-en-scène under investigation here, fulfill the role of a caption. A caption, unlike a title-card, engages in a direct dialogue with its visual accompaniment (as will be further elaborated upon in the analysis of Tout Va Bien). With this established, how do the captions of Figures 5 and 6 engage with the visual?

The already mentioned caption of Figure 5, “One must confront vague ideas with clear images,” is a static shot, held for just short of a minute, in which no characters are present for the duration. Over the shot, we hear Guillaume and an unnamed woman talking about their sub-lease and about the occupations of the woman’s parents. The caption serves to re-enforce Godard’s continued investigation of the cinematic language barrier via sound and image. Significantly (pun intended), the next appearance of the device, as seen in Figure 6, does not take place in a static space. While the shot begins without any characters present, emphasizing the text which translates as, “A minority on the right revolutionary path is not a minority,” Véronique quickly enters frame to open the door for Kirilov, who carries in their unconscious colleague Henri. As the scene progresses, Henri awakens and informs Véronique that he was beaten by another group of Marxist-Leninists to which an off-screen Guillaume responds “Being attacked by the enemy is a good thing because it proves that there’s a clear distinction that separates us.”

In this scene, the text provides a counter-point to the scene. The scene illustrates that the Marxist-Leninists in the apartment are being attacked by members of their own ideological group which, in the light of the quotation (no doubt a re-interpretation of Henrik Ibsen), would seem to put into question the objectives of the group in two ways. First, if the Marxist-Leninists were the true ideological minority, it is incredibly ironic that they are inspiring physical violence from within their own group, let alone be interpreted as being “the enemy” by Guillaume. Secondly, if followers of Marxist-Leninism had become so numerous to the point where they interpret other factions as being “the enemy,” the scene would also seem to question their status as a true minority as well.

Godard’s formal critique of Marxist-Leninism intersects with our investigation of his comic strip mise-en-scène, which seems to be utilised in a dialectical fashion. While the machine gun montage emits can be “decoded” (to borrow from the work of Stuart Hall) as an anti-imperialist message, but that is not to say it fully endorses the belief system of the Marxist-Leninists. In fact, Godard’s second aesthetic manifestation of this trend, the caption, would appear to do quite the opposite. Instead of underlining the action taking place in the setting, like the inserts in Made in USA, the caption, “The Minority…”,performs an interrogating action. While the degree of this interrogation could be argued, to conclude that the caption simply endorses the actions and ideology of the Marxist-Leninists is to ignore not only the mise-en-scène of the scene but the logic (both formal and narrative) of the film as a whole. With the hope of further expanding on this topic of comic strip mise-en-scène and the use of the caption, I would like to offer a concluding analysis of Godard and Gorin’s Tout Va Bien.

3. Tout Va Bien

“A superb formula from Jean-Luc Godard defined the cinema as ‘the art of making music with painting’. This definition applies itself equally to comics; at first because its images maintain as many affinities with painting as the shifting images of cinema; and because comics, in displaying intervals (in the same say as persistence of vision erases the discretization of the cinematic medium) rhythmically distributes the tale that is entrusted to it.”

-Thierry Groensteen (14)

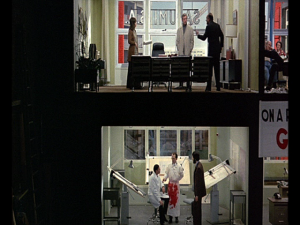

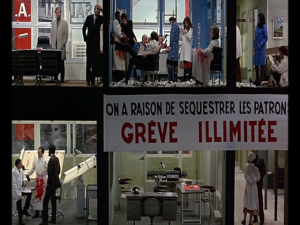

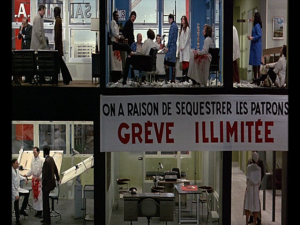

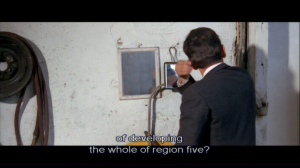

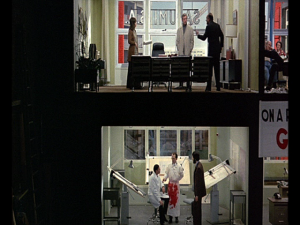

In one of their many Dziga-Vertov collaborations together, Tout Va Bien, Godard and Gorin move away from comic panel citation into a mode that fully mimics the lay out of the comic book page. The sequence that best exemplifies this shift is the tracking shot that pans across the interior of a sausage factory that is currently under siege by dissatisfied workers. While one could argue that it would be simplistic to simply write the scene off as a manifestation of this aesthetic, as the shot is also a citation of a shot from Jerry Lewis’ The Ladies Man (1961), Gorin informed me that it would not be unrealistic to cite the sequence as a form of comic strip mise-en-scène. Again, the tracking shot has been replicated using frame reproductions with noted times:

(Shot 1A, B, C, D: The Factory, 12:16-14:17)

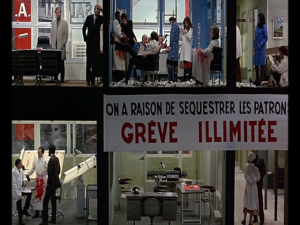

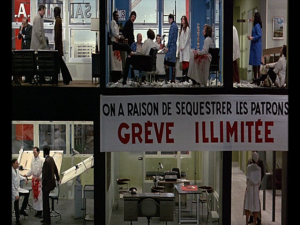

[Note: The sequence is to be read left to right, top to bottom (like a comic book) and that shots C and D take place as the camera is tracking back to its original spatial coordinate (hence the similarities between shot B and D).]

The mise-en-scène of this shot, which reoccurs several times throughout the film’s first segment, not only mimics comic book layout but makes playful use of what comic semiologist Thierry Groensteen describes above, in his citation of Godard, as the comic strips “rhythmic function.” To Groensteen, the rhythmic function manifests itself via the segmentation of time from panel to panel. Unlike film, whose segmentation of time remains fairly constant at 1/24th of a second, the duration between sequential frames in comic books varies. Moreover, as Scott McCloud illustrates, an individual panel can include a multitude of temporal durations with actions ranging from a split second to half a minute or longer) via the artist’s use of sound and dialogue. (15) The use of the grid structure by Godard and Gorin in this shot is complicated however. While the shot takes on the form of a comic book page with several different panels (the manager’s office, his secretary’s office, the staircase leading up to the second floor, etc), time is not interrupted by the black gutters of the grid à la a comic book. Rather, the shot reads like a temporally ambiguous panel, capturing actions in the different segments simultaneously.

Yet, while the shot does not obey “a rhythm that is imposed on it by the succession of frames,” it does have manifest a rhythm that is created via the use of a tracking camera, the actions of the actors within the segmented mise-en-scène, and music. (16) Much like the use of the icons and captions in La Chinoise, the rhythm of this shot also intersects with the Marxist investigation present within the narrative of the film. As the camera tracks away from the office of the manager (the upper left segment of the frame) containing the manager (Vittorio Caprioli), American journalist Suzanne (Jane Fonda), and her husband (Yves Montand), the characters in the cell become relatively motionless and their conversation comes to an end. Godard and Gorin, however, do not continue this trend of stationary staging. As the camera tracks into the other segments of the frame, the workers are allowed to continue their physical action and dialogue, united by their protest song (“If you keep on like this Salumi, the working class will kick your ass.”).

The second characteristic of comic strip mise-en-scène apparent in this shot, the caption presented via a printed banner reading, “Lock up the bosses. Indefinite strike,” does not function like its precedents in La Chinoise. First, the caption has no rational presence in the scene, whereas the captions in La Chinoise were established as being the product of the Marxist-Leninists painting the walls. The first time we see the banner, it is on the roof of the sausage factory in an establishing shot. During the tracking shot however, it stands where the wall of the factory would be, hanging impossibly within the frame of the building. More importantly, the caption does not serve as a formal means of interrogating the scene via their juxtaposition. In fact, the caption seems to underline and literalise the actions of the scene, much like the inserts in Made in USA. The workers have locked up the boss and they are pictured in an indefinite strike, courtesy of the framing and the duration of the shot.

With the form of this shot and its caption elaborated upon, what is the possible meaning to be derived from this sequence? On a second viewing, after experiencing the text as a whole, the shot appears to be a illustration of the question Suzanne later asks herself at the supermarket: “Where do we begin to struggle against the compartmentalisation of our lives?” The use of the “dollhouse” set serves to literalise this thought, placing the boss and workers in their separate cells while also containing the answer to Suzanne’s question: “Everywhere at once.” Through their singing and the unifying gesture of the shot’s lengthy duration and tracking, the workers are united despite their spatial segregation. Moreover, this link between Suzanne’s question and answer manifests itself formally as well. During the shot in which Fonda delivers dialogue, Godard and Gorin emulate the earlier lateral, temporally long, tracking shot in the supermarket. Colin MacCabe’s description of the supermarket tracking shot, “The content of politics is provided by an image which acts, in the most traditional way, as the visible evidence of the truth of Fonda’s voice-over,” would equally apply to its visual ancestor in the sausage factory. (17)

Via the progression of this engagement with comic strip mise-en-scène as analyzed in Made in USA, La Chinoise, and Tout Va Bien, Godard (and later, with his collaborator Gorin), appears to have come full circle in the use of the aesthetic. In Made in USA, Godard’s Lichtensteinian citation of the comic strip served as a means of literalising narrative cues, be it the assault of a woman (!…Bing) or the exploration of a mystery (“?”). La Chinoise, on the other hand, investigated the consequences of the translation of these aesthetic citations, engaging with the political ideology present in the iconography of a superhero and the juxtaposition of text and image. Finally, Tout Va Bien, while abandoning the direct citation of a comic panel, utilised the form of the grid and comic strip rhythm to provide a visual re-enforcement, much like Made in USA, but instead of literalising a narrative event, the “visible evidence” of the shot served as a means to realize a philosophical thought. Or, as the Marxist-Leninists in La Chinoise expressed via their wall captions: to provide a clear image to a vague idea.

Special thanks to Janet Bergstrom, Michelle Bumatay, and Jean-Pierre Gorin.

Endnotes

- Jean-Luc Godard, “Struggling on Two Fronts,” Cahiers du Cinéma 194 (October 1967), reprinted in Cahiers du Cinéma (1960-1968): New Wave, New Cinema, Reevaluating Hollywood, Ed. Jim Hillier (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1986), p. 297.

- Allen Thiher describes Alphaville as “the limits of experience have come to be defined by comic strip language”, yet simply equates “the comic strip side” (which he never really defines) as “a Brechtian form of ‘distanciation’.” See Allen Thiher, “Postmodern Dilemmas: Godard’s Alphaville and Two or Three Things I Know about Her,” boundary 2, 4.3 (Spring 1976), p. 950.

- Jean-Luc Godard, “Montage My Fine Care,” Cahiers du Cinéma 65 (December 1956), reprinted in Godard on Godard: Critical Writings by Jean-Luc Godard, Eds. Jean Narboni and Tom Milne (New York: Da Capo Press, 1972), p. 39.

- Will Eisner, “The Origin of The Spirit,” The Spirit (June 2 1940), in The Best of The Spirit (New York: DC Comics, 2005), p. 11.

- James Roy MacBean, “Painting, Politics, and the Language of Signs in Godard’s Made in USA,” Film Quarterly 22.3 (Spring 1969), p. 18.

- Daniel Yacavone, “Jean-Luc Godard and Roy Lichtenstein: Originality, Reflexivity, and the Re-Presented Image,” unpublished conference paper, pp. 3-4.

- Jonathan Fineberg, Art Since 1940: Strategies of Being, 2nd ed., (Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2000), p. 261.

- MacBean, p. 24.

- Author unknown, Captain America 78 (September 1954) (New York: Marvel Comics, 1954).

- Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (New York: Harper Perennial, 1994), p. 27.

- Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991), p. 191.

- Wheeler Winston Dixon, The Films of Jean-Luc Godard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997), p. 81.

- David Carrier, The Aesthetics of Comics (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000), pp. 33-34.

- Thierry Groensteen, The System of Comics (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2007), p. 45.

- McCloud, pp. 94-97.

- Groensteen, p. 45.

- Colin MacCabe, Mick Eaton, and Laura Mulvey, Godard: Images, Sounds, Politics (London