image: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/best-bela-tarr-films.jpg

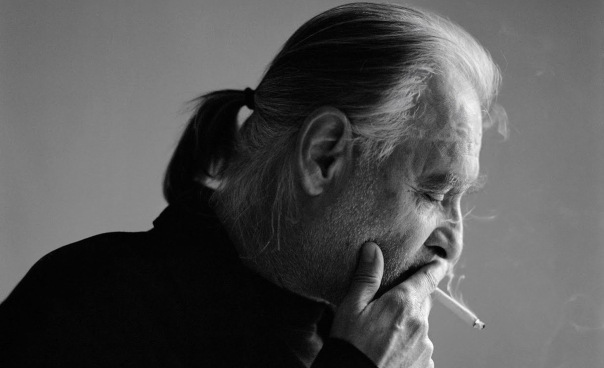

Bela Tarr, who has had a huge influence on contemporary filmmakers like Gus Van Sant and Jim Jarmusch, is one director whose films are more read about than watched. And it is not without a reason. Imagine a seven-hour-long movie made up of just 150 shots! Yes, he is capable of that.

A proponent of the slow cinema movement, where his comrades include the likes of Theo Angelopoulos, Andrei Tarkovsky, Miklós Janscó, Hou Hsiao-Hsien and Chantal Akerman, his films are often a difficult watch given their ponderously sluggish pace.

His camera often fixes its gaze on minor characters or seemingly insignificant details and frequently forgets to blink–lingering on a scene long after its contribution to the narrative is over. But then the purpose of such languid long shots is to make the audience look beyond the ‘purpose’. Because it is when you stop expecting the story to unfold and move forward, you actually start observing. It is in such prosaic, rudimentary details that the beauty of his shots truly reveals themselves.

His long takes are like Pieter Breugel’s paintings (who had a definite influence on the director) where everyone, each figure, even the smallest one in a crowd, has a distinct character. It is amid this mundaneness that he finds heroism and his characters, constituting mostly the marginalised, have-nots of the society, acquire their grace.

These signature long takes are also probably the most apt device to tell a story of everyday reality as these shots transport you to the scene of action (or inaction). It is as if you are sitting at one corner and watching a situation as and when (and if at all) it unfolds—you don’t have the option to select just the interesting bits. The audience goes through the same helplessness, ennui and the sufferings endured by the characters, and like their onscreen counterparts, come out feeling victorious.

Bela Tarr had once said in an interview: “I despise stories, as they mislead people into believing that something has happened. In fact, nothing really happens as we flee from one condition to another….All that remains is time. This is probably the only thing that’s still genuine — time itself; the years, days, hours, minutes and seconds.” And these lines probably sum up the very spirit of his approach towards films. Unlike in conventional cinema that stylishly weaves the significant moments, his films offer an uncut version of life, which is often meaningless.

Apart from the laboriously slow pace, what allegedly makes his films inaccessible is the context, which is in most cases his country’s disillusionment and inability to come to cope with the newly-emerged complexities of the post-communist era. His films are about the decay of social structure and the decline of small, poor, rural communities of East Europe.

In order to truly understand his film, you need to understand the Hungarian situation, its socio-political realities. But he often leaves the context unexplained. There is hardly any mention of where these stories are set, or what the historical background is. And these very aspects are also what make his films universal. Structured in the vein of fables and morality plays, his films talk about the dismal human condition and the disintegration of the moral fabric in general.

Nature plays an important role in the dark dystopian world of his films. And he is often compared with Andrei Tarkovsky. Indeed, like the Russian director he uses ‘dead time’ and landscape to create a sense of duration and distance but what they convey is drastically different. If Tarkovsky lingers on an object to reveal its sublime beauty, Tarr does the same to reinforce its very ‘ordinariness’.

And in an interview Tarr himself explained this: “The main difference is Tarkovsky’s religious and we are not. But he always had hope; he believed in God. He’s much more innocent than us—than me. No, we have seen too many things to make his kind of film. I think his style is also different because several times I have had a feeling he is much softer, much nicer….Rain in his films purifies people. In mine, it just makes mud.”

Most of Tarr’s stories unfold against the stark backdrop of a harsh unforgiving landscapes lashed by forces of nature. However, there is no pathetic fallacy. Nature, in his films does not reflect the mental state of the characters; it is what they physically endure on a day-to-day basis. He creates the atmospheric surroundings that his characters inhabit and draws the audience into it in an attempt to make them a part of the experience.

1. Family Nest (1979)

image: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Family-Nest.jpg

“This is a true story. It didn’t happen to people in the film, but it could have.” With these lines Tarr begins his first feature film, Family Nest. It is a story of family falling apart under the communist regime in Hungary during the ’70S.

Focusing on the severe housing shortage, it shows how a young couple along with their daughter is forced to live with the husband’s parents and siblings in a cramped up one-room apartment in Budapest. So many people sharing such a small space creates a volatile situation in the house and there are endless conflicts which eventually lead to despair and an intense sense of suffocation.

The couple’s desperate struggle to get a small government apartment so that they can escape the claustrophobia and salvage their relationship, and the incessant streaming of intense political propaganda through the television all reflect the tyrannical regime that is blind to the plight of its people. Tarr touches upon pressing problems like population explosion, severe housing shortage under the new laws and Government red-tapism

This raw kitchen sink drama is shot in a cinema verite style. Shot in shoe-string budget with non-professional actors, hand-held cameras, environmental sound (juxtaposed by occasional use of jarring pop music), on location shooting, and rough editing, it hardly predicts the stylisations of Satantango or a Werckmeister Harmonies (although the ‘shabby bar’ makes its first appearance in this film).

This documentary-like realistic style of his early films has often been compared to that of John Cassavetes’s (an influence Tarr vehemently refuses). Tarr uses tight close-ups to heighten the claustrophobia and often pans to highlight seemingly arbitrary objects, but the choreographed camerawork that was to become his signature in later years, are conspicuously missing in this film.

Also, such a crowded film can hardly make room for the long stints of silence that populate his more mature films and here apart from dialogues, Tarr gives his characters monologues to vent out their feelings, giving an impression of how lonely they are in their individual struggle—maybe staying in such close proximity is alienating them from one another.

image: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Family-Nest-1979.jpg

There is nothing ‘ambiguous’, ‘cosmic’ or ‘metaphysical’ in this blisteringly realistic drama. However, even at a young age of 22, the world Tarr and the Family inhabits is essentially bleak—where the society in general is rotting from inside, there is oppression, male-domination, hypocrisy, poverty, hopelessness, angst and a general decay in moral values. Although not a great work of art in itself Family Nest reflects the humble beginning of the great auteur.

In his next two films, The Outsider and The Prefab People, he continued more or less in the same vein—thematically as well as stylistically.

The Outsider, his first film in colour (the second and the last being Almanac of Fall) and centres around a bohemian alcoholic musician, who was once thrown out of the Conservatory, takes up various jobs but can’t sustain any because of his drinking problems. He is not any good when it come to relationships either—he insists of paying child support for a child that is probably not his and this effects his present relationship. The film shows the trails and turbulations of the working class and an individual’s futile attempt to fit in.

And in Prefab People, where Tarr first introduced professional actors, we see another young married couple’s slowly decomposing relationship under the economic pressures. The film moves back and forth as Tarr shows the couple stuck in a vicious cycle of complaints and indifference, reel after reel it is the same thing in a slightly different pretext. Arguably the best among his ‘socialist realist’ films, this kitchen sink drama reflects the strife, struggle, and stagnation of the working class in the Hungary of the late ‘70s.

2. Almanac of Fall (1984)

image: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Almanac-of-Fall-1984.jpg

“Even if you kill me, I see no trace, this land is unknown, the devil is probably leading, going round and round in circles.”

With these lines of Alexander Pushkin begins Bela Tarr’s Almanac of Fall. The intense chamber drama oozing post Iron Curtain angst is set in a claustrophobic run-down apartment inhabited by five people: Hedi, the owner of the house, her son Janos, her nurse Anna, and two male boarders, Miklos (Anna’s boyfried) and Tibor (Janos’s former teacher).

The characters are almost clichés: an ill and volatile old woman, a jobless, drunkard son who lives off his mother’s wealth; a conniving young woman who has no qualms in sleeping around with the men (and she beds all three) to forward her own design; a scheming Lothario; and an ex teacher and once a man of good repute now reduced to a petty thief.

The story is a simple one: Hedi is the aged and wealthy matriarch and the other four are after her money and to get that they are vying for her allegiance. In the process the self-consumed characters eves-drop, conspire, manipulate, backstab at the slightest opportunity, falling into new lows each day. The characters share tumultuous relationships, from verbal abuses to violent physical assaults they go through everything, but no one even attempts to escape the situation or the hell house. And this reminds of Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit.

Although not regarded as a major work in his oeuvre, the film is important in understanding the transition—from gritty realism of his earlier films to the extreme formalism of his late masterpieces.

But what makes this film significant in itself is its mise-en-scene. Tarr uses non-naturalistic lighting scheme and unconventional camera angles to tell this story of moral decay, treating each scene as an independent set piece.

Tarr’s voyeuristic camera goes everywhere—it peeps from behind wall, doors, window; it takes the characters from the top (a god’s eye view from the ceiling) and from under (wide-angle shot taken through a transparent floor, creating an eerie illusion of the characters floating mid-air.

image: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Almanac-of-Fall.png

The film (one of his two major colour features) uses an expressionistic colour palette. The shots are lit in blue greys and red oranges with the colour isolating the two characters from each other. By creating such compartments for the characters he stresses upon the fact that despite their physical proximity, one cannot really enter the other’s mental space. However, Tarr doesn’t colour-code his characters. The colours usually reflect their emotional state. In this respect the last sequence deserves a special mention.

Tibor is arrested for stealing Hedi’s bracelet and the remaining members celebrate that they are one competitor down. Shot under pristine white light, it probably symbolises that the rainbow colours of sin that this white contains within itself will soon hit another prism and show their true colours—eventually the cycle to conspiracy, debauchery, corruption, betrayal will continue. It will all go “round and round in circles”.

This is reinforced in the last shot. Once Tibor is taken away by the police, the remaining inhabitants prepare for Anna and Janos’s wedding. But in the final scene we see Miklos partnering Anna in a dance while Janos and Hedi stare at the camera blankly, hinting that the marriage was just a sham and the power-game within the house will continue as before. Tarr chooses the song for this final dance carefully–it is a version of Que Sera Sera, what will be, will be—symbolising the fact that amid this deception and decay, life will go on.

3. Damnation (1988)

image: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Damnation-1988.jpg

“I don’t care about stories. I never did. Every story is the same. We have no new stories. We’re just repeating the same ones. I really don’t think, when you do a movie that you have to think about the story. The film isn’t the story. It’s mostly picture, sound, a lot of emotions. The stories are just covering something. With “Damnation,” for example, if you’re a Hollywood studio professional, you could tell this story in 20 minutes. It’s simple. Why did I take so long? Because I didn’t want to show you the story. I wanted to show this man’s life.”

Nothing explains his films better than these lines. Damnation is an age-old story of love and betrayal. Karrer, a recluse and an alcoholic, lives in a small half-abandoned mining town (we are never told about its exact geographical location) and every evening lands up in a shabby cheap bar called Titanik. He is in love with the bar singer, who is married.

One day the bar owners offers him a smuggling job which he passes on to the husband (Sebestyn) so that he can spend some quality time with the singer (who is never named). However her affection for him is as fickle as it is for her husband. Upon Sebestyn’s return, there is a confrontation between the two men. And at the end, a disillusioned Karrer turns in everyone to the police.

image: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Damnation.jpg

The plot is minimal, dialogue is sparse, and pace is glacial with long takes and the camera moving in extreme low motion. The film is a trailer to what Tarr achieves in his later masterpieces, Satantango and Werckmeister Harmonies. It marks a transition (subject wise and stylistically) from his earlier realist dramas filmed mostly using hand-held cameras to what was to become his trademark—the black and white treatment, extremely long shots, languid camera movement.

The most poignant scene is the last one where Karrer is down on his fours confronting a street dog in the middle of a dirt pile while it continues to pour. Tarr ends the shot with Karrer, having forced the dog to retreat with his animalistic behaviour, walks away. The dolly shot shows rain falling on the muddy landscape as Karrer crosses the frame, Tarr continues shooting the mud and slush before fixing his gaze back on the dirt pile. The effect it has on the audience is of despair as it dawns that there is no way to escape this ruthless world—there is no respite from the muck life produces.

4. Sátántangó (1994)

image: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/satantango.jpg

In the beginning there was…well an 8-minute long shot of cows grazing in a muddy landscape. The background is equally interesting—that of barns and crumbling buildings. For the first one minute, the camera refuses to make any movement, when it does it leisurely tracks the herd rarely panning sideways. We see a cow vainly trying to mount on another; the mooing gets louder, the herd crosses the muddy field and after a rather long walk finally disappears behind the row of houses.

That’s all that happens! But seemingly insignificant and tedious opening shot sets the mood of Bela Tarr’s magnum opus that will last for almost seven hours during which we will see a group of characters wander and trudge through the same mud and slush of the rain-lashed landscape. The bovine bunch reflects the collective identity of these people; and like the brainless cows they will blindly follow one another and eventually all will end up in the same rut. Also, through this shot, Tarr acquaints the audience with the place these characters inhabit, an almost deserted, small, squalid village of 1980s Hungary where everything is in a shambles—houses, moralities and the society in itself.

Based on Laszlo Krasznahorkai’s book by the same name, it is not a story about a particular character but a group of people, more so, a story of amorality digging its roots into the society loosening its very fabric.

The community farm has collapsed and the few remaining inhabitants have just sold off their community-owned cattle and are waiting to receive a lump-sum amount. Once they get the money, they will all leave the village. However, within this small group, a few are planning to hoodwink the rest and abscond with more than their fare SHARE

IMAGE: HTTP://CDNCACHE1-A.AKAMAIHD.NET/ITEMS/IT/IMG/ARROW-10X10.PNG .

.

Suddenly, news spreads that Irimas, the master swindler, who they had thought to be dead, is on his way to the village. The villagers get apprehensive that he might again sweep them off their feet with his grand plans and take away the money. And yet they wait for his arrival and eventually fall into his trap losing not only the CASH

IMAGE: HTTP://CDNCACHE1-A.AKAMAIHD.NET/ITEMS/IT/IMG/ARROW-10X10.PNG but whatever little property they had.

but whatever little property they had.

The story is not a long one. What makes it run for seven hours is Tarr’s narrative style (which acted as an inspiration for Gus Van Sant’s Elephant). In-keeping with Laszlo’s slow-paced, minutiae-laden baroque narrative, Tarr films the story using languid camera movements and extremely long takes (the film consists of just 150 shot!). The pace of the film also gives the audience a sense of the dull and dreary life in such villages.

image: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/S%C3%A1t%C3%A1ntang%C3%B3-1994.jpg

The non-linear structure of Laszlo’s book takes inspiration from the six-step-forward and six-step-backward (it has a total of twelve chapters, 6 move forward and 6 go back) movement of a Tango. It reflects the very nature of the society—like in a tango, for each six steps forward, it goes six steps back. And Tarr retains the same rhythm. Not only is the film is broken into six sections, where each can be viewed as a separate episode, making for an easier view; but he creates the tango with his choreographed camera movements and long takes and use of overlapping time–the story moves backward and forward; multiple storylines unfold within the same time frame and intersect; one event is observed from perspectives of different characters.

One of the best examples of this, and also one most poignant scene in the film, is when a little girl named Estike cruelly kills her cat with rat poison for no apparent reason. She then takes the dead cat with her and walks towards the woods where she finds that her brother has duped her off her little savings. She confronts him but realising that it’s a lost battle, relents and trudges her way back to the village where she briefly stops to watch people dancing at a small pub. She keeps walking, still carrying her cat, and around morning arrives in front of a dilapidated building where she consumes the same poison she gave her beloved cat and waits for death to embrace her.

Next we see the Satan’s Tango–a group of inebriated people are dancing haphazardly to the tune of an accordionist in a bar. We slowly realise it is the same Danse Macabre we had seen through Estike’s eyes a few minutes back. It is reinforced by a close-up of Estike, gazing inside the bar from one of the windows. The effect is profound. Knowing what tragic fate awaits her, we wish something in the scene changes, and the little girl is saved.

The film ends with the ‘doctor’– a curious character who maintains a notebook on each of the eight characters of the group, documenting their lives in detail—returns home after spending several months in a medical facility where he ended up after suffering a fall on his way to refill his STOCK

IMAGE: HTTP://CDNCACHE1-A.AKAMAIHD.NET/ITEMS/IT/IMG/ARROW-10X10.PNG of fruit beer. As he sits by the window staring at the empty streets, he suddenly hears the rings of a church bell—this is exactly where the film had begun, with him hearing the ringing of the bells and the whole story now seems like a figment of his imagination. But was it?

of fruit beer. As he sits by the window staring at the empty streets, he suddenly hears the rings of a church bell—this is exactly where the film had begun, with him hearing the ringing of the bells and the whole story now seems like a figment of his imagination. But was it?

5. Werckmeister Harmonies (2000)

image: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Werckmeister-Harmonies-2000.jpg

Laszlo Krasznahorkai’s 1989 novel The Melancholy of Resistance serves as the source material for this film. Again the setting is a small, bleak, unnamed village-town of Hungary, but we get a respite from the rain and muck, it is winter. The film begins with a quintessential Tarrian shabby country bar. It is closing time. The bar owner splashes water in the fireplace snuffing off the last flames. János Valuska, a popular village do-gooder walks in.

A total solar eclipse is due and the villagers are apprehensive. In an attempt dispel the myths surrounding the event, with the help of three drunk men, he acts out the changing position of the planets that will cause the natural phenomenon. And ends his case with the promise that at the end “there come light again”. Till the sun rises again, all we need to do is bear with the darkness.

As he walks out of the bar and walks through the deserted street, the chiaroscuro created by street lights is stunning. As the shot progresses, Valushka’s silhouette becomes smaller and smaller until darkness engulfs the whole frame. What Valushka had acted out few moments earlier, Tarr creates with his lighting—an allusion of the eclipse. It foreshadows that something ominous is about to happen—“There is husbandry in heaven”, as Shakespeare’s Banquo would have said.

Evil penetrates the town in the form of a circus truck casting gargantuan shadow over a row of houses—a scene reminiscent of the monster shadow of the balloon vendor in The Third Man.

In the HOTEL

IMAGE: HTTP://CDNCACHE1-A.AKAMAIHD.NET/ITEMS/IT/IMG/ARROW-10X10.PNG where rumours have started trickling in that a circus is coming to town with a huge stuffed whale and ‘Prince’—a mysterious character(never seen in the movie) who is supposed to have dark powers. In nearby villages entire families have started to disappear. Are these all urban legends or tell-tale signs of an Apocalypse?

where rumours have started trickling in that a circus is coming to town with a huge stuffed whale and ‘Prince’—a mysterious character(never seen in the movie) who is supposed to have dark powers. In nearby villages entire families have started to disappear. Are these all urban legends or tell-tale signs of an Apocalypse?

What unfolds is a story of eclipse of a different kind—initially, the mundane goings-on are overshadowed by the enthusiasm to catch a glimpse of the artificial whale and then the ever-elusive Prince’s shamanistic powers palls the morals of the locals. The sleepy hamlet becomes a hotbed of anarchy—there are riots, revolts, unrests and eventually people go on a mad rampage and attack the town hospital. All this is seen through the eyes of Valushka, who wanders around the streets. He is the modern-day reincarnation of the Shakespearean wise fool.

image: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Werckmeister-Harmonies.jpg

The 145-minute-long film has just 39 shots and moves smoothly through a black and white world in languid pace through an assortment of long shots, framing shot, extreme long shots, tracking shots and close-ups. The film is replete with Tarrian signature long takes that reflect the novel’s Faulknerian sentences and his camera’s fixation of gazing at people till they reach the vanishing point continues.

It is film of brilliantly executed set pieces–from the first scene of Valushka acting out the movements of the solar system, to the most poignant one in the movie—that of the mob walking resolutely from the town square to the hospital where they ransack each ROOM

IMAGE: HTTP://CDNCACHE1-A.AKAMAIHD.NET/ITEMS/IT/IMG/ARROW-10X10.PNG bludgeoning patients on the way, only to be confronted by a naked, shrivelled, old man in the shower stall, and retreat without a word.

bludgeoning patients on the way, only to be confronted by a naked, shrivelled, old man in the shower stall, and retreat without a word.

By the end, Tarr seems to suggest that when the society falls in gloom and despair, and dark forces take over, all we can do is endure until it passes; for as Valushka had promised: After the eclipse “there come light again”.

The whale brings with it ambiguity and the story has been interpreted in different ways—that of Capitalist invasion, the turbulent political scenario of Hungary where Communism is breathing its last, life behind the Iron Curtain, the breakdown of old social system and apprehensions about the new one, forces with ulterior motives stoking the fire of revolution and misleading the mass. But ask the director, and he dismisses all the political allegory by saying: “I just wanted to make a movie about this guy who is walking up and down the village and has seen this whale.”

6. The Man From London (2007)

image: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/The-Man-From-London-2007.jpg

This time Tarr picked an unlikely suspect–a pulp fiction by Belgian writer Georges Simenon. Titled L’Homme de Londres, the book was already made into films by Henri Decoin in 1943 and by Lance Comfort in 1947.

The story centres on a railway switchman who appropriates a suitcase full of British sterling by chance. In an attempt to ensure a better future, he slowly becomes a true-blue criminal shunning his family and morals on the way.

While explaining his unusual choice Tarr says: “it deals with the eternal and the everyday at one and the same time. It deals with the cosmic and the realistic, the divine and the human, and to my mind, contains the totality of nature and man, just as it contains their pettiness.” With his mastery in creating stark black and white images and haunting chiaroscuro and use of slow tracking shots and hypnotic camera movements, noir might seem just the right genre for him.

image: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/The-Man-From-London.jpg

But while you might marvel at his techniques, you will miss the chills-down-your spine moments that are part of a film noir experience. Tarr treats Simenon’s page-turner almost the same way he would treat a Krasznahorkai, replete with Faulknerian sentences—instead of using his style to create a noir film, maybe his attempt was to adapt a crime thriller to a genre that he himself has created and mastered.

For the first time the setting and the language is essentially non-Hungarian and the characters are not representatives of a particular social class. But, the formalistic aesthetics reflected in the film, are at best, a diluted version of the Tarr of Werkmeister Harmonies. Nonetheless it is interesting how Tarr re-imagines the much-adapted crime thriller and fits it into his own mould.

7. The Turin Horse (2011)

image: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/The-Turnin-Horse-2011.jpg

Tarr’s ninth and last film (another collaboration with Laszlo Krasznahorkai) begins with a narrator telling the apocryphal tale of how Neitzsche went mad after watching an obstinate horse being mercilessly whipped on the streets of Turin. It ends with a question: But what happened to the horse?

So, does Tarr give you an answer in what follows next? Not really! May be it is the same horse, may be a different one. But the story (or for that matter, most of Tarr’s stories) unfolds in a Nietzshean world where God is dead.

It is a story of how a horse, crucial to the day-to-day existence of his master, suddenly turns stubborn and refuses to eat, drink, and work. It is also a story of a father-daughter duo who keeps on taking the lashings of fate, until they are completely beaten down. But unlike in the case of the eponymous horse that was eventually saved by the German philosopher, no one, not even God comes to their rescue. It is a bleak Nietzschean world where there is no hope, no comfort, no respite– where God is dead.

image: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/The-Turnin-Horse.jpg

If Samuel Beckett’s Wait0069ng for Godot is a play where nothing happens twice, in Bela Tarr’s Turin Horse, that happens six times. We see these two characters, living in a decrepit house in the middle of a storm-lashed heath, going about doing their daily chores in a ritualistic manner— the girl dresses and undresses her father (whose one hand is paralyzed), then she fetches water from the well, boils potatoes, both eat one each for each meal with brandy and try to persuade the stubborn beast.

Each day is the same and Tarr’s suffocatingly slow camera captures six such consecutive days in the life of this father-daughter duo– each time from a slightly different angle– during this period their world completely crumbles. We never get to see the seventh day, maybe Ohlensdorfer and his daughter suffered the same fate. It all seems like a parody of God creating the world in six days. Maybe like God on the seventh day they too decided to take a break—a break from life itself.

On the seventh day, Tarr also signed off from filmmaking. He had announced Turin Horse as his swan song and it is a distillation of his nihilistic worldview.

Author Bio: Ananya Ghosh is a senior copy editor with one of India’s leading newspapers. An obsessive-compulsive traveller and an occasional travel writer, she is also a film addict who watches every movie with an analytical eye. She is as enthusiastic to catch the first day show of a Bollywood blockbuster as she is to attend four back-to-back screenings at a Buñuel or a Bela Tarr Retrospective. Although she is having a passionate fling with Lars von Trier films at present, Cary Grant comedies remain the true love of her life.

Read more at http://www.tasteofcinema.com/2014/filmmaker-retrospective-the-slow-cinema-of-bela-tarr/#yu1QU2GxDhXXC6E4.99